The following article about the Center Harbor barn survey project appeared recently on NewHampshire.com:

December 23. 2017 5:33PM

Historic barns connect NH to its rural past

CENTER HARBOR — As family farms continue to fade, a Lakes Region group is determined to identify and preserve historic barns that once stood at the heart of agrarian life here.

The Center Harbor Heritage Commission has partnered with volunteer Rick Kipphut to document every barn 50 years or older in town. The project is a joint effort with the New Hampshire Preservation Alliance’s “52 Barns in 52 Weeks” campaign to increase awareness of the need to preserve these symbols of the state’s rural roots.

Farmers built barns to shelter livestock and store hay and harvest. The structures evoke a sense of tradition and permanence, and embody the close connection the people who built them and worked in them had to the land, said Kipphut. He has surveyed 15 barns in Center Harbor already, has 20 more on his list and is on the hunt for more.

Recently, Kipphut documented the circa 1876 Longwood Farm barn on Route 25, next door to Camp Restaurant. It once housed a prize-winning herd of Guernsey cattle owned by Edward Sereno Dane. Kipphut also surveyed the 1903 Keewaydin dairy barn on Route 25B, a landmark that stands out for its unusual tile silo.

After making contact with barn owners via postcard, Kipphut makes arrangements to visit the property. On average, he spends three to four hours at a barn, making notes and occasionally answering questions the present owner might have about its construction, use or history.

Sometimes Kipphut is on the receiving end of information as owners regale him with their barn’s provenance and providence through generations. “People have been very gracious. They are connected to their barns, their history, and are proud of them,” Kipphut said.

During the survey, Kipphut fills out a farm reconnaissance inventory that documents construction materials and features. He photographs each barn inside and out and the pictures are digitally embedded in the completed report, which is shared with the property owner and will be added to Center Harbor’s “Cultural and Historical Resources Inventory” as part of the update of the town’s master plan.

Kipphut also informs owners as to the resources available to help maintain their historic barn. Signed into law in 2002, RSA 79-D authorizes municipalities to grant property tax relief to barn owners who can demonstrate the public benefit of preserving the structure and who agree to sustain it for a minimum of 10 years.

Kipphut graduated with a master’s degree in historic preservation from Plymouth State University in May. He came to historic preservation late in life after teaching business at Quinnipiac University.

When he’s not working as a staff member in the library at PSU, he puts his research skills to work, researching barns. “Everything is online when it comes to deed research. It’s very helpful,” he said. Before taking on the Center Harbor project, Kipphut surveyed the massive barn that is now home to one of the North Country’s most popular tourist spots and eateries, Polly’s Pancake Parlor in Sugar Hill. Property owners Kathie and Dennis Cote approached selectmen with information from the survey and were able to prove the public benefit of preserving the circa 1886 structure. Following a public hearing, the couple was granted a tax break. “It not only safeguards a historic structure but a shared landscape resource,” Kipphut said of RSA 79-D.

On a recent Saturday as he set up a camera and tripod, Kipphut said barns are so much more than a nostalgic remnant of a bygone era. They are a slice of history that’s uniquely New Hampshire and worth appreciating, he said. The landmark structures not only make the past present, they reflect changing farming practices, construction techniques and technologies. The cultural value of a barn can’t be considered in isolation, Kipphut said. Many are intimately connected with the families who built them and are intertwined with the surrounding community. Weathered wood siding, a grand cupula, cut granite blocks, hand-hewn beams, mortise and tenon joinery, plank flooring scarred by decades of use — it all contributes to the special character of a barn.

A barn crowded by suburbs is not a barn in the same sense as a barn in its natural setting, amid other farm buildings, or so says Kipphut. He gestures across the street where off in the distance a barn stands handsomely with a forest behind and a pond in front. Preservation of barns can’t be divorced from preservation of the setting, he explains. As part of his work, Kipphut climbs hayloft ladders and navigates steep narrow staircases, photographing every detail. He revels in unique features, a hay trolley, the telltale marks of a draw knife on hewn beams, square hand-forged nails. Each detail is a clue as to the age and history of the barn, he says.

If you own an old barn and would like additional information or would like to participate in the survey, you can contact Rick Kipphut at 726-0925 or via email at researchthepast@gmail.com. There is no cost.

Barn Survey in Center Harbor

PSU Historic Preservation alumnus Rick Kipphut (’16G) has been busy surveying barns as part of Center Harbor’s effort to document the town’s historic structures. Here’s a recent press release describing Rick’s project:

Barn recently surveyed in Center Harbor.

Seeing Old Houses

Sometimes property owners need fresh eyes. Faced with the never-ending maintenance of a home or rental property, they lose sight of significance and destroy materials in exchange for the promise of reduced upkeep, operating costs, or property taxes.

Over the past year, I have toured five local historic houses, each complete with ells, barns, and in one case a three-story chicken house. All are imperiled. Three of the main houses, two ells, one barn, and the chicken house are threatened with demolition; the two other houses have seen protracted renovation.

The attachment of current owners to these properties varies widely in sometimes unpredictable ways. Often those owners with the longest history are most ready to call in the bulldozer, and they may be just as ready to call it off. You never know.

As I explore the structures, I learn about the owner’s time in that space and their plans for the future. It is a privilege. In return, I do not proselytize. By pointing out features along the way, even in mundane materials like timbers, granite, and fasteners, I just try to impart some new appreciation for overlooked objects. I share information gleaned from deeds, census forms, maps, and photographs. And when asked, I offer advice or followup research—while also trying to convey two tenets of preservation: retain historic materials and find reversible solutions.

This morning at the bank I ran into one owner. We had last talked on a foggy day in January down at the property. His latest tenants had just moved out, and demolition loomed. His greeted me with a challenge: “Tell me why I shouldn’t just tear this thing down.” That’s a quote.

Today he thanked me again for showing him a place he did not know existed—even after his three decades of ownership. Photographs from the 1890s, taken before some unfortunate alterations to the ell, showed an inviting, gabled farmhouse and relaxing porch on a shaded lot. Andrew Jackson Downing might have liked it. Rather than demolish this house, the owner grew more interested. It had possibilities. And despite his years and his tremors, he climbed an extension ladder and painted it this spring. Then he found new tenants.

Whether the other two threatened houses will meet with similar outcomes remains to be seen. I fear one will be lost to neglect, and I hope one will survive as the first and only brick house in town. In the preservation world, that would be a win.

Belmont Mill

The Belmont Mill NH State Register Nomination was prepared for the Belmont Heritage Commission. The mill was constructed in 1834 and was central to the development of the town of Belmont. Factory Village (as Belmont was once called) was built around the Badger Mill, and the village evolved into today’s Belmont as the Badger Mill grew into the Gilmanton Mill and then into the Belmont Mill.

This mill complex was the driving force in Belmont’s economy throughout its transition from a locally-capitalized cotton mill in the 1830s to a highly mechanized hosiery factory with world-wide distribution in the 20th century. In 1970, the Belmont Mill was largely abandoned when the Fenwick Hosiery Mills (who had purchased the mill in 1956) consolidated in Laconia.

This mill complex was the driving force in Belmont’s economy throughout its transition from a locally-capitalized cotton mill in the 1830s to a highly mechanized hosiery factory with world-wide distribution in the 20th century. In 1970, the Belmont Mill was largely abandoned when the Fenwick Hosiery Mills (who had purchased the mill in 1956) consolidated in Laconia.

On August 14, 1992, there was a devastating five alarm fire at the Belmont Mill complex. As a result of the fire, many of the outbuildings at the mill were demolished and a Save the Mill Committee was started in an effort to preserve the 1834 main building. In January 1996, the first Plan NH Charrette was held to focus on possible future uses of the Belmont Mill and how to fund the project. Through a series of grants and a grass-roots community effort, the mill was renovated between 1996-1998.

Those efforts to save the Belmont Mill have been widely recognized in the preservation community, and the adaptive reuse project has received many awards. For more information, visit the Belmont Village Revitalization site or see the Laconia Daily Sun article announcing the State Register listing.

[Post by Mae Williams, PSU ’14G, preservation consultant on the listing]

Concord Gasholder

CONCORD N. H. GASHOLDER FACES UNCERTAIN FUTURE

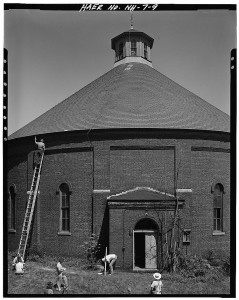

After more than two years of apparent inaction, owner Liberty Utilities has recently announced that it will soon decide whether to repair or demolish the well-known but damaged gasholder house in Concord, N. H. The 1888 brick structure is the last gasholder house in the United States to retain its interior floating tank. The building serves as the logo of the Northern New England Chapter of the Society for Industrial Archeology (SIA).

After more than two years of apparent inaction, owner Liberty Utilities has recently announced that it will soon decide whether to repair or demolish the well-known but damaged gasholder house in Concord, N. H. The 1888 brick structure is the last gasholder house in the United States to retain its interior floating tank. The building serves as the logo of the Northern New England Chapter of the Society for Industrial Archeology (SIA).

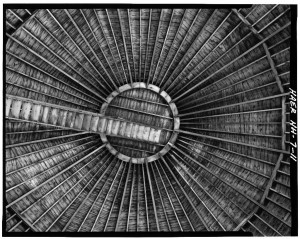

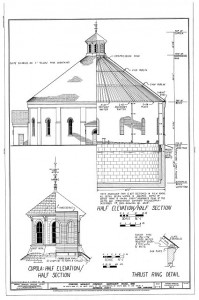

Built for the Concord Gas Light Company (founded 1850) to supplant smaller gasholders with lesser capacities, the 1888 structure is 86 feet in diameter and 28 feet high to the top of its brick walls, and had a maximum storage capacity of 120,000 cubic feet. The riveted gasholder tank weighs 80,000 pounds and floated in a subterranean cistern holding 800,000 gallons of water. W. C. Whyte of New York City built the structure, and Laurel Iron Works of Philadelphia fabricated its enclosed wrought iron tank. Both companies were specialists in gasholder design and construction.

The Concord gasholder house was the site of the inaugural meeting of the Northern New England Chapter of SIA on July 26, 1980. Two years later, the chapter recorded the building for the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) with a 25-member team assembled by the late William L. Taylor of Plymouth State College, now PSU. Chief of HAER Eric DeLony and Smithsonian curator Robert M. Vogel advised the crew, and a survey and planning grant from the New Hampshire State Historic Preservation Office provided financial support. Taylor published a summary history of the gas company and the gas holder in the SIA journal IA 10:1 (1984): 1-16.

The gasholder stored coal gas until 1894, followed by carbureted water gas until 1952, when the then-owners switched from manufactured gas to natural gas.

Although unused, the building remained in excellent condition until 2013, when a storm-toppled tree crushed a section of its conical wood-framed and slated roof. The impact damaged the wooden thrust ring at the base of the roof and the supporting masonry wall below. The owners left the roof unrepaired as winter approached, prompting the New Hampshire Preservation Alliance to declare the gasholder house one of the seven most endangered historic properties in the state in October 2013.

Liberty Utilities hired a contractor to place a temporary patch on the roof in September 2014, but a year later has announced that the temporary work is at the end of its effective life and that the company must soon decide whether to restore the building or to demolish it and clean up the site. Local officials regard the building as an icon of the New Hampshire state capital and are hoping to meet with Liberty Utilities representatives to seek a way to preserve the structure.

[This article was written by PSU Historic Preservation professor James Garvin and originally published in the Fall 2015 (Vol. 36, No. 2) newsletter of the Society for Industrial Archeology – New England Chapters.]

Bridge Demolition

On July 31 the Concord Monitor reported that replacement of the historic Sewall’s Falls Bridge would begin on August 3, 2015.

The Sewall’s Falls Bridge is a two-span, riveted Pratt through-truss crossing the Merrimack River on Sewall’s Falls Road in Concord, NH. The bridge was designed by John William Storrs, a New Hampshire bridge designer, and constructed in 1915. It replaced a wooden covered bridge and utilizes the granite pier and abutments from that earlier bridge.

In 1988, the Sewall’s Falls Bridge was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

“Sewall’s Falls Bridge is Concord’s last surviving example of a bridge design by New Hampshire’s most eminent bridge engineer of the early twentieth century, a designer who maintained his practice in Concord and served the city in many other ways.” — James Garvin, 2005

The Sewall’s Falls Bridge was permanently closed to vehicular traffic on December 1, 2014. Pedestrians and bicyclists continued to use and enjoy the bridge through July. The City of Concord maintains a Sewell’s Falls web site showing the progress of the Sewall’s Falls Bridge Project, which is scheduled for completion in December 2016. Mitigating the demolition of the historic bridge, part of the Section 106 review and Memorandum of Agreement with the NH Division of Historical Resources, the old bridge’s history will be presented on a plaque within Sewall’s Falls Park. A small portion of the bridge will also remain on exhibit.

[ Post and photos by Audra Klumb, ’14G ]